A big THANK YOU for all the e-mails I got about Part 1 of this story! It’s always nice to know that people are reading and enjoying your work.

Fair warning for anyone opening this issue in your e-mail and running behind: You need to read my recent piece in the New York Times and then catch up on Part 1.

“What’s Santa Got To Do With It?” (Part 1)

Part 1 explains how some people use “aesthetic sublimation” to cover for personal prejudice. To give this practice a historical frame, I introduced the origins of the debate between “political music” and “absolute music” involving Richard Wagner.

Part 2 focuses on the economic aspects of music-making that led to an emergent split between “high” and “low” art in the United States at around the same time.

You can imagine where stuffy critics thought Santa Claus fell along that spectrum!

Frank Johnson

Practically anyone who knows my work also knows that I think the exclusion of black musicians from conventional histories of classical music is criminal on its face. But it’s doubly criminal because scholars have had a vast wealth of black musical historiography and bibliography at their fingertips for 150 years.

Beginning with James Monroe Trotter’s 1878 book Music and Some Highly Musical People, scholars of black music (by which I mean music of Africa and the African Diaspora) have meticulously documented the activities of black musicians to preserve this history against the tide of overwhelmingly white narratives.

Will Marion Cook, Maud Cuney Hare, Frederick and Mildred Hall, Eileen Southern, Samuel Floyd, Jr., Dominique-René de Lerma, Helen Walker-Hill, Josephine Wright. These are only a handful of the legendary bibliographers and scholars of black music-making whose work challenges most conventional narratives of classical music.

You might also note that many of them are women.

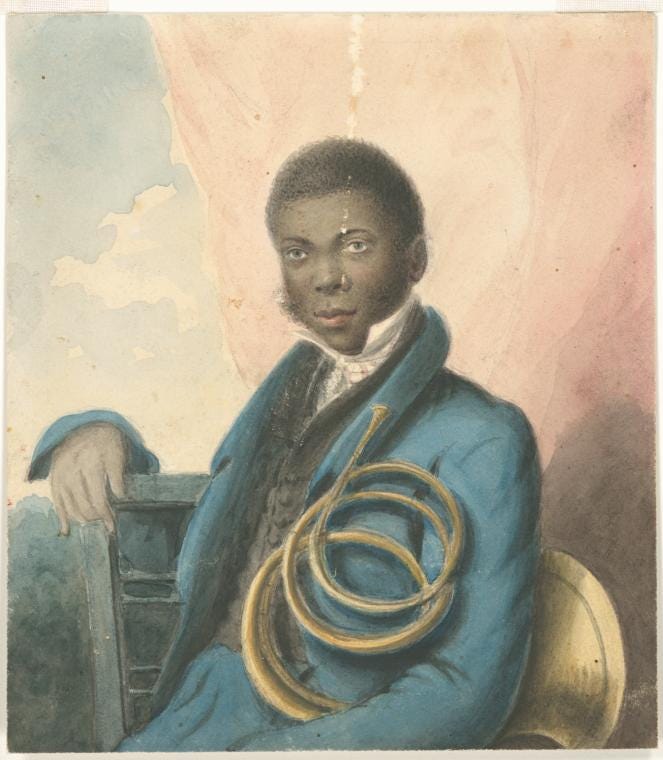

With that in mind, our Santa Claus story picks up in the late 1830s with African American bandmaster Francis (Frank) Johnson, who was well known in Fry’s hometown, Philadelphia, for organizing and directing popular dance concerts.

(Picture available in the NYPL Digital Collections)

I first learned about Johnson in a 1977 article by Eileen Southern published in The Black Perspective in Music. Southern explains that Johnson traveled to London with his band in November 1837 and immediately started giving concerts—talk about hustle!

They started programming music that had proven popular at home. Here’s an ad in the Morning Post of London from December 13, 1837 giving a sample of their repertoire:

You can see that he programmed a mix of genres, from opera overtures and arias to patriotic and popular songs, all arranged for his brass band. This style of programming, called a “potpourri concert,” was very common, even for orchestras.

While in London, Johnson and his band encountered a version of the potpourri concert on steroids called a “promenade concert.” In this setup, the stage, seats, and floor would be arranged so that audiences could either lounge or dance during the show instead of just sitting still. In London, the first conductor to lead one of these shows was someone named “Mr. Pilati.”

Here’s an excerpt from one of Pilati’s playbill:

The name I’ve highlighted—Musard—is critically important.

Conductor Philippe Musard had practically invented the promenade concert in Paris a few years earlier; Pilati had been the concertmaster of his orchestra. London critics generally felt that Pilati’s shows didn’t quite live up to Musard’s originals, which are described in this Musical World review from July 1837, just before Johnson arrived:

Whoa! Fragrant fountains? Mirrors? Mozart? Sign me up! Pierre Boulez’s “rug concerts” with the New York Philharmonic had nothing on this! Johnson soaked it all in during the winter concert season in London—from Pilati’s shows to buzz about the real thing in Paris. And when he returned to Philadelphia loaded with music and fresh ideas for his next concert series, guess who would report on them for the local press…

That’s right—William Henry Fry!

Johnson in Philadelphia

As Eileen Southern explains, Johnson returned to the United States in June 1838 and embarked on a “western” tour that included Saratoga Springs, Buffalo, Toronto, Detroit, and Cleveland. (Remember the USA went only as far west as Illinois in 1838!)

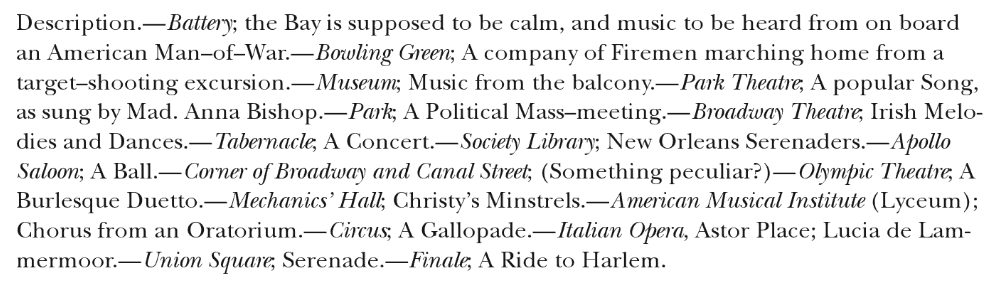

By the start of the winter concert season, he was ready to launch a new series in Philadelphia, where he announced his first promenade “à la Musard”:

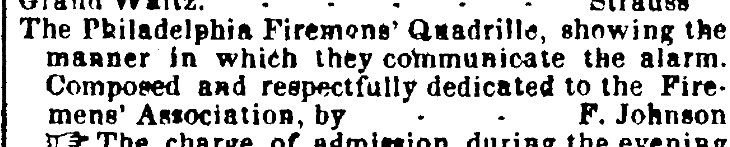

Unlike Pilati, Johnson programmed pieces that were meant to tell stories. In a dance number called The Firemen’s Quadrille, for example, audiences could expect this:

(Public Ledger, Jan. 7, 1839)

Not a lot of information, but enticing! Now check this out—same show:

This is intriguing. Here we have a five-part series of waltzes designed to tell a specific story about a sleigh ride at Christmastime! Hmm, sound a little familiar?

These waltzes have been published in a modern edition, and there is nothing particularly extravagant in the music (for the time). But the key point to remember is that Johnson meant to evoke these pictures in the minds of his audiences.

(PS. For you history nerds: The reference to Kuffner is a mistake in the advertisement.)

Over time, Johnson introduced more elaborate theatrical elements into his shows.

The Bird Waltz:

The Philadelphia Fireman’s Quadrille:

The Railroad Gallop:

Here we have music that is clearly designed to entertain, not only by offering nice dance music but also a compelling theatrical story. At the ultra-low price of twelve-and-a-half cents per ticket, audiences in the thousands went bonkers for these shows.

There is no possible way that William Henry Fry, then in his late 20s, wouldn’t have been aware of these concerts. He’d been covering musical events for his father’s newspaper, the National Gazette, for a couple of years already and would continue to write for the Public Ledger after 1841. When Johnson died on April 9, 1844, it’s highly likely that Fry wrote this personal message about his impact on the city:

An International Marketplace

“So what, Shadle? This is 10 years before the Santa Claus brouhaha.”

Since undergraduate music history surveys have traditionally focused only on composers and works, I imagine many people don’t have much context for understanding Frank Johnson’s concert series. Unlike orchestras today, ensembles like those led by Johnson and Musard were 100% profit-driven, and they often competed with rival ensembles. Johnson’s introduction of theatrical elements into his programs was a direct result of Musard’s Parisian rivalry with Louis Antoine Jullien.

Consider this commentary about Jullien’s Parisian shows in the London Musical World from August 1836, just a couple of years before Johnson heard Pilati in London:

That’s right—Jullien had stagehands intentionally set fire and shoot weapons at his concerts! He also programmed Beethoven and Mendelssohn. Adding theatrical experiments was a tried and true strategy for Jullien, so Johnson moved in this direction to establish an entrepreneurial niche in the USA.

Developing this niche also included borrowing music from other successful conductors. In addition to theatrics, Johnson also began programming waltzes by Johann Strauss, Sr., a conductor who was leading his own orchestra in Vienna. As musicologist John Spitzer has explained, entrepreneurial orchestras like those run by Musard, Jullien, Pilati, and Strauss created an international marketplace for all kinds of orchestral music, from dances to symphonies, while appealing to a huge public. They offered something for nearly everyone, even people who preferred the “classics.”

Jullien Comes to America

Some of the most successful European orchestras in this mold, including Strauss’s, embarked on American tours in the years after Johnson’s death in 1844, and they continued to cater to local taste by including tailored theatrical elements. The conductor of the Germania Orchestra, Carl Lenschow, even wrote a theatrical piece called Panorama on Broadway specifically for American audiences.

Here’s a description from an 1849 Boston playbill:

(Copied from Nancy Newman, Good Music for a Free People, 131)

Meanwhile, the Germania Orchestra also became known as one of the finest interpreters of Beethoven and Mendelssohn that Americans had ever heard. The group performed roughly 900 times between 1848 and 1854, allowing audiences in many US cities to become relatively familiar with an incredibly wide range of orchestral music. The New York Philharmonic, in contrast, performed four to six concerts per year.

But the biggest coup of all occurred when Louis Antoine Jullien announced that he would embark on a US tour in 1853. Jullien had fled from money troubles in Paris around 1840 and set up shop in London to reboot his orchestra. Over the next thirteen years, his group became one of the most popular musical ensembles throughout Great Britain and scored season after season of major profits.

Why a coup? At the time, people understood that Jullien’s approach to programming—performing a wide range of repertoire at a virtuosic level—was political. With low ticket prices, he was bringing musical enjoyment to people of every social class and every taste.

So where better to spread this gospel than the United States? From the London Musical World in November 1852:

Of Jullien’s hearty reception in America there can be little doubt. The inhabitants of that vast continent are too intelligent, too anxious to be amused and ready to be taught, too much imbued, in short, with that indomitable “Go a’head” feeling, which, under the less familiar name of “enthusiasm,” has been one of the ruling motives of his public conduct and the great secret of his prosperity, not to sympathise with him and advance his interests. It is only among nations as free as they are populous and might, that such a man as Jullien can hope to find the elements of success. He has found them in England, and he will find them in America.

Nothing would have made William Henry Fry happier, especially since he had just returned from Paris ready to forge a new destiny as a composer.

Conclusions

To summarize where we’ve been:

From my piece in the Times, we know that William Henry Fry and George Frederick Bristow got into a major tussle with the New York Philharmonic in 1854 over the orchestra’s refusal to perform music by American composers. Jullien’s performance of Fry’s Santa Claus: Christmas Symphony on Christmas Eve, 1853 helped spark the conflict.

From Part 1, we know that Richard Wagner brought an emerging aesthetic conflict about the politicization of musical style to new heights in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Fry was living in Paris at the time and soaking it up.

From Part 2, we know that Fry left for Paris in 1846 thinking about Frank Johnson’s theatrical concert experiences, probably attended Musard’s concerts, and returned to New York in 1852 just as Jullien announced he would be touring the United States. It was a match made in heaven.

Thinking about these items together: Group social relations, politics, musical style, and the musical economy all fueled the conflict between Fry, Bristow, and the Philharmonic. As I’ll explain in the final part of this series, these same issues continue to shape discussions about the future of classical music today.

Stay tuned for the microscopic analysis of Santa Claus you’ve been holding out for!!!

A Postscript

Isn’t it incredible that Duke Ellington, an entrepreneurial and versatile bandleader in the tradition of Johnson and Jullien, also wrote a pictorial tour of Harlem?

Music City Spotlight: Speaking of jazz, check out my brilliant colleague Ryan Middagh’s latest remote video, “Sorry Not Sorry.” Wow!!! So sad I can’t hear them live.

In the queue: “What’s Santa Got To Do With It,” Part 3

Content fueled by Badbeard’s Microroastery (Portland, OR).

If you like what you read here: