Despite all the bad news developing around us, it’s shaping up to be another exciting year for Florence Price.

The International Florence Price Festival

First, I’m pumped about the inaugural International Florence Price Festival coming up this August on the University of Maryland—College Park campus. Both the School of Music and the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center at UMD have been extraordinarily generous in their support of this fledgling independent organization by offering venue space and grant-funding opportunities. THANK YOU!

The festival program committee assembled a stellar lineup of presentations, which means artists and scholars submitted a stellar lineup of presentations. Although I’m not on the committee, my understanding is that they received far more than they could accommodate given the time and space constraints. It’s been indescribably exciting to see the outpouring of interest in Price develop in real time. (And I hope anyone whose work could not fit in the program will continue to stay in touch about it.)

Here are some of the items on tap at the festival:

A duo vocal recital featuring Christine Jobson (soprano) and Darryl Taylor (countertenor)

A lecture-recital hosted by the Ben Holt Memorial Branch of the National Association of Negro Musicians (featuring Karen Michèle Walwyn, Marquita Cooper and others)

A panel discussion honoring the legacy of pioneering Price scholar Dr. Rae Linda Brown, moderated by her sister, Dr. Carlene J. Brown

A lecture-recital on Price’s string music by the Apollo Chamber Players

And much more! Keep an eye on the website and social media for updates.

Also, if you believe in supporting this kind of work, please consider making a tax-deductible gift to the Festival or volunteering to help. Truly, no amount is too small.

Florence Price Returns to Orchestra Hall

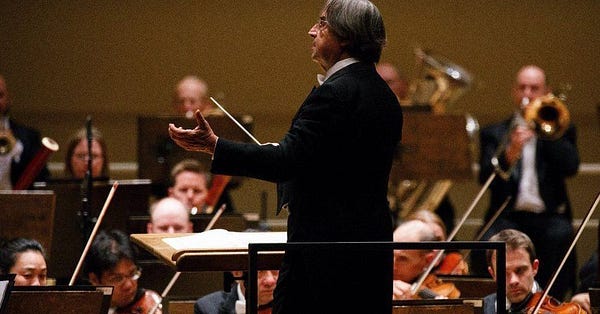

When the Chicago Symphony Orchestra announced that it would be performing Price’s Third Symphony under Riccardo Muti in its 2019-2020 season, KUSC’s Brian Lauritzen, a vocal advocate of expanding the repertoire, gave a huge thumbs up:

Michael Cooper of the New York Times also captured the sense of occasion by highlighting this performance over all others in his tweet about the season:

I immediately marked the concert on my calendar and breathed a sigh of relief when I noticed it was just after our spring semester! #WillTravelForFlorencePrice

Now that it’s six weeks out, here are some thoughts about the momentous event.

Most people who’ve encountered Price and her music know that the Chicago Symphony premiered her Symphony in E Minor in 1933, making her the first African American woman to have a symphony performed by an orchestra.

(Photo from the CSO Archives site linked above)

As I’ve written elsewhere, it’s very curious that a concert devoted to highlighting the achievement of Black musicians (composers and performers—note Roland Hayes and Margaret Bonds as soloists) would open with an overture by John Powell, an openly anti-Black racist and eugenicist. (No, really.) I’ll say more in my next set of Price reflections, but this is how predominantly white organizations deploy whiteness as a “meta-privilege” (as Barbara J. Flagg has called it) despite their best intentions.

It’s also a curious fact that this event was paired with another concert from the night before called an “American Night.” It featured pieces by Henry Hadley, Deems Taylor, and George Gershwin, with Gershwin himself as soloist.

(Photo from the CSO Archives site linked above)

The pairing says a lot about who “counted” as fully American in 1933. As I wrote in my last newsletter issue, Black musicians are simply speaking the truth when they talk about how orchestras can easily represent pillars of white supremacy. More on all that forthcoming from Samantha Ege later this year!

Muti’s performance of Price’s Third Symphony won’t exactly be her CSO homecoming. Conductor Mei-Ann Chen, director of the Chicago Sinfonietta, made her CSO subscription debut in 2013 with a performance of Price’s Mississippi River, a work with an elusive origin that may never have been performed in her lifetime.

Many of you know that I co-edited a collection of the beloved Chicago Sun-Times critic Andrew Patner’s reviews of the CSO dating from 1991 to his sudden death in 2015. I was curious if Andrew had anything to say about Price’s belated CSO homecoming in 2013 and found this commentary:

Strong pre-concert performances by local tenor Henry Pleas and pianist Charles Hayes of Price song settings also point to the need to hear more of her large catalog more regularly.

If only he could know how far things have come since then! I can only imagine that he’d have brought his encyclopedic knowledge of Chicago’s rich history to an unforgettable interview with Muti and would glow in the sun of Price’s symphony.

(He also would have said something about the attractive pairing of William Grant Still’s unjustly neglected and wonderfully tender Mother and Child for strings. Check out this luscious performance of the original for violin and piano.)

For those of you in or around the Chicago area, please support the orchestra’s decision to perform Price’s music on the main subscription series (in April, not February!) by purchasing a ticket. I’m honored to be participating in a pre-concert panel with my friends Dr. Tammy Kernodle and Dr. Alisha Lola Jones (Florence Price all-stars!), as well as Dr. Johann Buis and Phillip Huscher (CSO pre-concert anchors!) before the shows on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. If you come, please say hello!

New Publications

Publisher G. Schirmer has been hard at work expanding the available Price catalog. The biggest recent addition has come with the assistance of musicologist John Michael Cooper, who has provided a stream of critically edited works for solo piano. (And the wonderful Lara Downes has been recording them! — and recording them!)

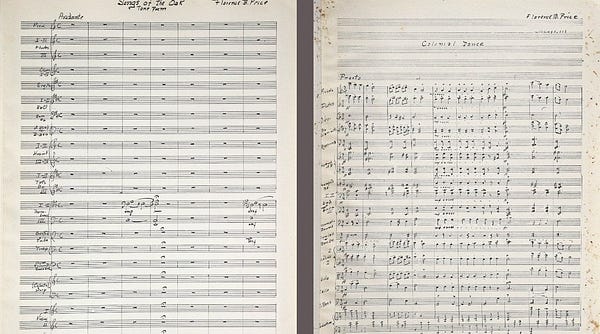

In orchestral music news, G. Schirmer recently announced that it had acquired manuscripts to three pieces—Songs of the Oak, Colonial Dance, and the Piano Concerto in One Movement—from a private collector in rural Illinois.

For die-hard Price fans who know her tone poem The Oak, the new piece, Songs of the Oak, is entirely different. No performances are on the official schedule…yet. I’m curious to know more about the oak as inspirational symbol for Price!

Colonial Dance is not new, though it has not been recorded and is therefore not well-known anyway. The new published score is almost identical to the MS score available in the Florence Price Papers Addendum at the University of Arkansas. A performance at the University of Louisville is happening later this month.

The piano concerto, in contrast, is one of Price’s most beloved and popular pieces. Prior to the major discovery of manuscripts in 2009—described by Alex Ross in 2018—the only available score for the concerto was a piano reduction. The eminent composer Trevor Weston re-orchestrated the piece, and his version became the standard. (Karen Walwyn performed as soloist for the world premiere recording.)

The manuscripts in this new collection are Price’s original orchestration, which she presumably used in the many performances that took place during her lifetime. The 2009 discovery included several original parts, but these were damaged by mold and mildew and would be difficult to reconstruct fully. The new acquisition will allow G. Schirmer to publish the full orchestration as Price conceived it.

My hope is that both versions will remain in wide circulation. Dr. Weston played an essential and vital role in the construction of Price’s legacy in the years leading up to the 2018 explosion, and his beautiful version deserves to be a part of the repertoire.

Meanwhile, you can hear the premieres of the “new old” version in July at the Oregon Bach Festival and the Ravinia Festival, where Lara Downes will be performing it (along with Paola Prestini’s Hindsight: Let me See the Sun) with the OBF Chamber Orchestra and the Chicago Symphony, respectively.

(And Downes’s moving new album, Some of These Days, is available for pre-order.)

Hiding in Plain Sight

I’ve been working on a Major Article about Price for four years now and have run into some brick walls in the peer-review process—some understandable, some not, as these things go. It’s back under review, and I should hear the result very soon.

For better or worse, people are going to do what they want with Price’s music, biography, and legacy while a lot of clarifying scholarship is in the pipeline. This frustrates me, and my next set of reflections on Price will go over this point in finer detail. For now, I want to share a story about how the coordination of scholarship and performance can change people’s lives for the better.

Late last month, the Black Hills Symphony Orchestra in Rapid City, South Dakota performed Price’s First Symphony along with Kodály’s Háry János Suite and Dvořák’s Cello Concerto—an interesting grouping that explores national musical identity. I gave a post-concert talkback by videoconference and witnessed how narrative frames can play a crucial role in shaping our concert experiences.

One of my article’s key interventions into Price scholarship concerns her family’s racial identity. Here’s an extended excerpt:

The trajectory of Price’s life mirrored that of many African Americans of her generation. As an Arkansan born shortly after Reconstruction, she experienced Jim Crow’s tightening grip firsthand and joined the Great Migration by moving with her family to Chicago amid intense racial violence. She quickly forged strong bonds with other black musicians, especially women, on the South Side, where she resided for the rest of her life. Though accurate as far as it goes, this narrative conceals the nuanced challenges Price, her mother, and her daughter faced as racially ambiguous women. Previous biographers have acknowledged that Price’s mother was of mixed racial heritage but have not explored how this racial ambiguity shaped her family’s perceptions of their own racial identity. As historian Allyson Hobbs has explained, racially ambiguous individuals of the era “wrestled with complex questions about the racial conditions of their times” and “fashioned complex understandings about their places in the world.” All three women experienced these feelings and responded differently.

Allyson Hobbs’s extraordinary book A Chosen Exile is a rigorous yet accessible study examining individuals of African ancestry who crossed the color line and “passed” as white between roughly 1865 and 1965. She uses the term “racially ambiguous” to describe these individuals, since a lighter skin tone destabilizes the prevailing binary racial logic and provokes unique challenges within a racist society.

(Scholars such as Lori Tharps, JeffriAnne Wilder, and others have also explored how the diversity of physical features like skin tone and hair texture among people of African ancestry should play a role in the intersectional analysis of Black womanhood. See the following comment on Facebook from Dr. Alisha Jones.)

Building on Hobbs’s insights, my biographical approach to Price adds the nuance of racial ambiguity since at various points in their lives, Price, her mother, and her daughter all confronted the choice to cross the color line and responded in ways that had profound effects on their individual and collective futures.

Consequently, when I discuss Price’s biography with audiences, I don’t sugarcoat the difficulties for Black women under Jim Crow—racist violence, legal restrictions on movement and activity, health challenges, and so on. Nor do I hide the fact that, as a racially ambiguous woman, Price’s ultimate choice to self-identify as Black when she returned to Arkansas from Boston, where she had been passing occasionally as Mexican, set into motion the more familiar aspects of her biography that have already come to light in the work of Barbara Garvey Jackson, Rae Linda Brown, Samantha Ege, and others. (Mexicans were considered “white” in the legal framework at the time.)

Back to the post-concert discussion in Rapid City: I began by asking the audience how they liked the symphony, and everyone loved it. It sounded comfortably familiar, they said, because it is lush, colorful, and melodious like most famous orchestral music. I added that it’s squarely within the larger symphonic tradition but Price used the third movement (conventionally a scherzo) to introduce the African-derived dance known as “the juba” as a way of articulating the piece’s connection to her own heritage within the larger African diaspora. She also based much of her melodic material on the contours found throughout the Negro spirituals.

Someone wanted to know more about Price’s early life and career, which was my cue to talk about race, womanhood, and Jim Crow. After answering, I fielded a few more unrelated questions, but then a woman spoke up and said (I paraphrase):

This is the first-time I’ve been to the concert hall and heard music by an African American woman—and someone who looks like me. THANK YOU for telling us her story, especially the parts about being mixed-race. As a mixed-race person with lighter skin, the question of passing is something I have to confront all the time, especially in a predominantly white area like Rapid City. To get in touch with my African heritage, I’ve studied African dance, and I felt it in the third movement. This is the first time I’ve come to the orchestra and felt seen. I’m going to be telling others about this experience for a long time.

The story was deeply moving. I thanked her for sharing her experiences and said that I was grateful for the opportunity to be a part of it. Very little is more rewarding for me than engaging with people who are comfortable enough, or feel liberated enough, to express their authentic selves in a musical space, maybe for the first time.

Thinking back, one of the most important lessons for presenting organizations to take from this anecdote is that diverse programming, though a good start, doesn’t account for our deep-seated human need to feel connections with other people. Music alone can help foster those connections. But the stories we tell in conjunction with the experience can make all the difference in the world when it comes to developing what Aubrey Bergauer calls “a sense of belonging.”

Telling these stories the right way is what organizations should strive for.

Music City Spotlight: You can hear students and faculty from Vanderbilt and Belmont, including my musicology colleague Jim Lovensheimer, perform for our “Clara Schumann at 200” party last September! Part 1, Part 2

Issues in the Queue: Racial Justice, Florence Price, and Rev. Dr. Alisha Jones (Florence Price in 2020, Part II); Environmental Justice and Dr. Rachel Beckles Willson; Lessons from Gabriela Lena Frank

Content fueled by Badbeard’s Microroastery (Portland, OR).